By Tom McGehee

By Tom McGehee

Museum Director of the Bellingrath Home

Walter Bellingrath always wanted his guests at his “Belle Camp” retreat to sign in on old hotel-type registers. (The practice continues to this day.) In the 1936 register, an entry written in Mr. Bellingrath’s distinctive hand states: “Our first meal in our new home on the Glorious Fourth of July, 1936: Mr. and Mrs. Walter D. Bellingrath.” No mention is made of the other guests, or of what the meal consisted of, but the date remains a significant one.

The Bellingrath Home had taken about 18 months to build, amid architect delays and changes to the original design. For example, the alcove in the dining room was an afterthought. It was created after the house was begun, in order to accommodate the recently purchased English sideboard that Mrs. Bellingrath feared might dwarf the room.

Mrs. Bellingrath relied on a Birmingham decorating firm, Hawkins-Israel Co., Inc., for some assistance. The firm was one of the first in the South and offered “one stop shopping” in the 1930s, with departments for design, paint and painting, fabrics, upholstery workrooms, carpets and electric fixtures.

Invoices from Hawkins-Israel offer a fascinating look into the expenses involved in furnishing a great house in the mid-1930s. The carpets and runners came to a grand total of $4,602.24, reminding us today that these were luxury goods in that era. In comparison, the custom-made wooden Venetian blinds installed in every window and French door came to only $891.50. The firm hung all of the mirrors and pictures free of charge.

Invoices from Hawkins-Israel offer a fascinating look into the expenses involved in furnishing a great house in the mid-1930s. The carpets and runners came to a grand total of $4,602.24, reminding us today that these were luxury goods in that era. In comparison, the custom-made wooden Venetian blinds installed in every window and French door came to only $891.50. The firm hung all of the mirrors and pictures free of charge.

While the invoices reflect that Hawkins-Israel handled window treatments, carpets, paint colors and even custom-made lamp shades, Bessie Bellingrath handled the rest. During her frequent trips to New Orleans, she found and purchased the dining table and chairs that had once been owned by Sir Thomas Lipton (1850-1931), a 22-piece double parlor suite from a Pontalba apartment, and the sparkling crystal chandeliers for the living and dining rooms.

Mrs. Bellingrath’s bedroom furniture came from a private home on Audubon Boulevard in New Orleans, while the ornate cornices above the French doors in the dining room came from a circa 1856 house on Conception Street in downtown Mobile.

China to fill the Butler’s Pantry came from B. Altman & Company as well as the Black Knight China Company on New York’s Fifth Avenue. The spectacular sterling silver centerpiece for the dining room table came from Royal Antiques in the French Quarter at the hefty price of $475.

China to fill the Butler’s Pantry came from B. Altman & Company as well as the Black Knight China Company on New York’s Fifth Avenue. The spectacular sterling silver centerpiece for the dining room table came from Royal Antiques in the French Quarter at the hefty price of $475.

The summer of 2020 is a good time to visit the Bellingrath Home and recall that July evening 84 years ago, when an excited couple had the first of many memorable meals in their dream home.

By Tom McGehee

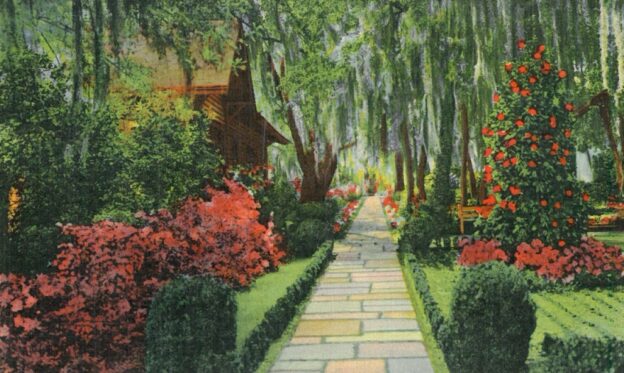

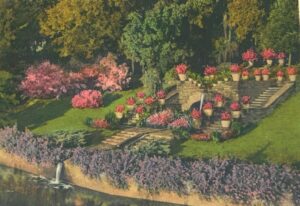

By Tom McGehee These images were soon joined with colorful “linen cards,” so called for the high rag content, making them look like cloth or linen. Walter Bellingrath Edgar, a great nephew of Bessie Bellingrath and a trustee of the Bellingrath Morse Foundation, recently donated a letter regarding these later, hand-tinted cards. It was written by his uncle, Will Dorgan, to Mrs. Charles Keating of Ohio, who had requested a set of 12 cards depicting the Gardens.

These images were soon joined with colorful “linen cards,” so called for the high rag content, making them look like cloth or linen. Walter Bellingrath Edgar, a great nephew of Bessie Bellingrath and a trustee of the Bellingrath Morse Foundation, recently donated a letter regarding these later, hand-tinted cards. It was written by his uncle, Will Dorgan, to Mrs. Charles Keating of Ohio, who had requested a set of 12 cards depicting the Gardens. In the letter, dated May 1, 1939, Mr. Dorgan explained that “These cards are made in Switzerland and arrived in New York on March 28th and should have reached us the following week. For some unexplained reason they have been held up in the customs house in New York for inspection and it has been difficult for us to find out just why this unusual delay.”

In the letter, dated May 1, 1939, Mr. Dorgan explained that “These cards are made in Switzerland and arrived in New York on March 28th and should have reached us the following week. For some unexplained reason they have been held up in the customs house in New York for inspection and it has been difficult for us to find out just why this unusual delay.” On the outside of the envelope containing the postcards is a poem written by George B. Rogers, the architect who designed Bellingrath Gardens and Home:

On the outside of the envelope containing the postcards is a poem written by George B. Rogers, the architect who designed Bellingrath Gardens and Home: