Upcoming Event!

Bellingrath Gardens and Home was the creation of Mr. and Mrs. Walter Bellingrath. The Gardens first opened to the public on April 7, 1932. Mr. Bellingrath placed an ad in the Mobile paper, announcing that anyone who would like to see the Spring Gardens could do so free of charge. After an overwhelming response, the couple decided to keep the Gardens open year-round, beginning in 1934.

About The Bellingraths

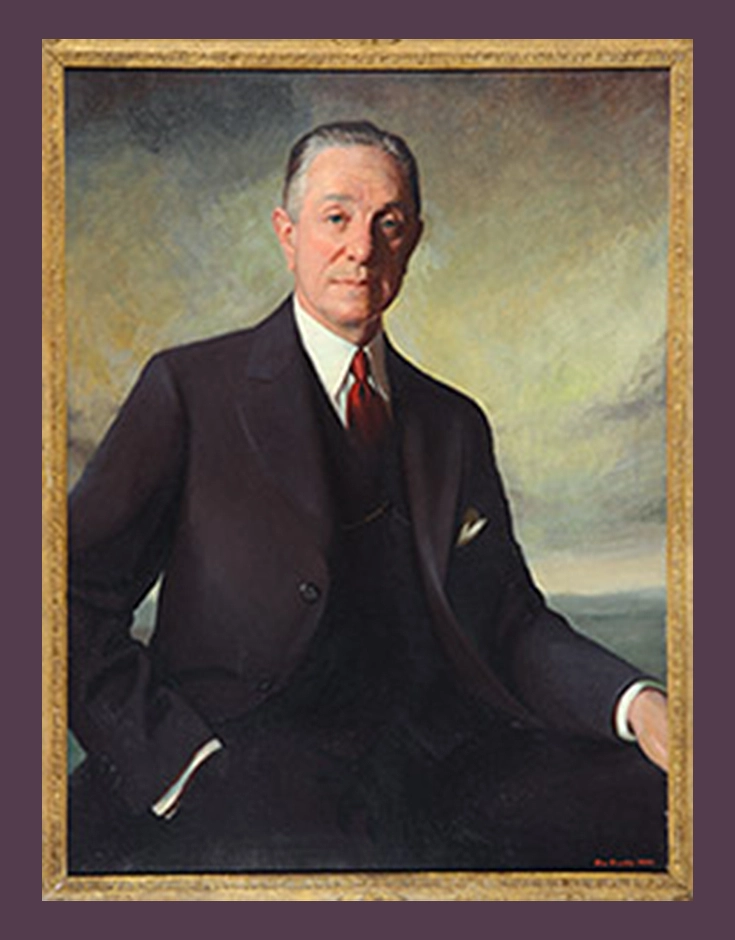

Walter Duncan Bellingrath (1869-1955)

Though a native of Atlanta, Walter Bellingrath was raised in the small town of Castleberry, Alabama, where he got his start at the age of 17 with the Louisville and Nashville Railroad. His first job was as a station manager, and his duties included sending and receiving telegraph messages. His old telegraph key sits on his desk in the Bellingrath Home as a reminder of those simple beginnings with one of the South’s most generous benefactors.

In 1903, Walter and his older brother, William, heard about an opportunity to purchase a new franchise to sell bottled Coca-Cola in southern Alabama. The franchise territory stretched down to the Gulf Coast, and when it was determined that they should split the territory, Walter took Mobile since, as he later joked, he liked to fish. The Mobile Coca-Cola Bottling Company became one of the most successful in the United States. Walter Bellingrath’s business interests stretched to owning the National Mosaic Tile Company, serving on the board of the First National Bank, and owning a warehousing company. He was also an original founder of the Waterman Steamship Company of Mobile.

His interest in his adopted hometown led to his long association with the Mobile Chamber of Commerce. On two different occasions, it was Walter Bellingrath who wrote a personal check to cover the entity’s annual financial shortfalls. He was a member of Central Presbyterian Church, where he served as a deacon.

Walter Bellingrath married Bessie Mae Morse of Mobile in 1906. The couple had no children. After his wife died in 1943, Bellingrath dedicated the rest of his life to working on the Gardens she had worked so hard to create. “These Gardens were my wife’s dream,” he once said, “and I want to live to see that dream come true.”

In 1955, at his death at the age of 86, his estate had been converted over to the Bellingrath Morse Foundation to oversee the operation of his beloved Gardens and to open his Home to the public. To this day, profits beyond those needed to operate Bellingrath Gardens and Home benefit Central Presbyterian Church and St. Francis Methodist Church and provide scholarships at Huntington College in Montgomery, Alabama, Stillman College in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, and Rhodes College in Memphis, Tennessee (formerly Southwestern University).

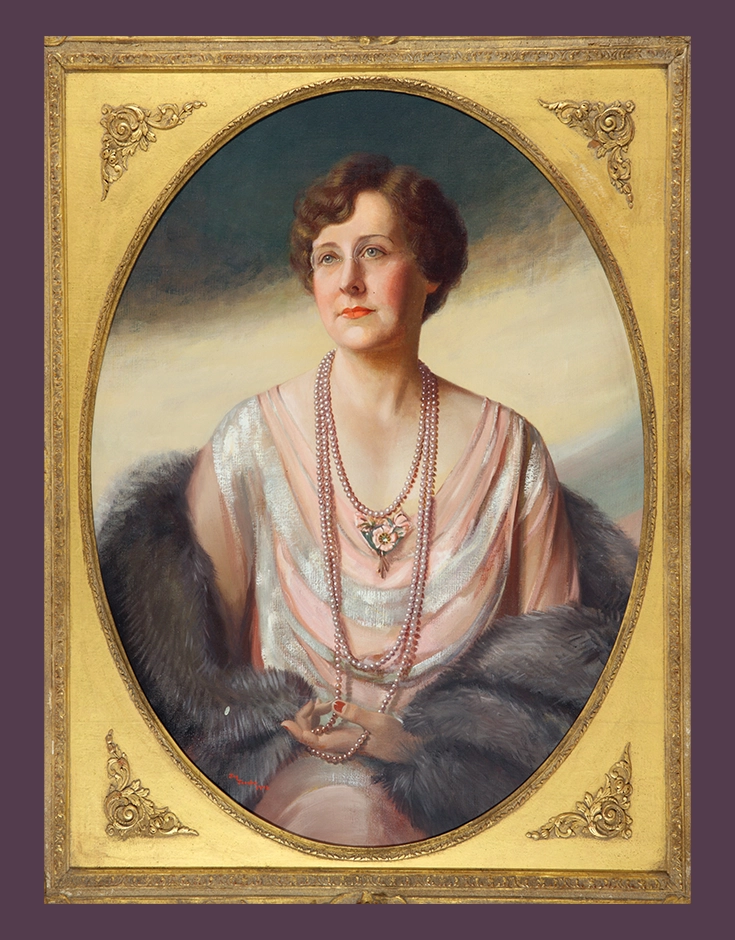

Bessie Mae Morse Bellingrath (1878-1943)

Bessie Morse Bellingrath was one of nine children born to Sewell and Alice Morse of Mobile. Mrs. Bellingrath’s early interest was in the arts, but practicality led her to be a stenographer. Her last job was with the Mobile Coca-Cola Company. She married its owner, Walter Bellingrath, in November 1906.

Mrs. Bellingrath’s love of gardens developed quickly. The couple’s South Ann Street home was long admired for its extensive gardens and became the basis for Mobile’s famous Azalea Trail in 1929. It was her idea to start planting azaleas at “Belle Camp,” an otherwise rustic fishing camp. Her husband always credited her genius for the creation of Bellingrath Gardens.

As the economic depression worsened, friends quietly kept Mrs. Bellingrath aware of families in need. She would appear, checkbook in hand, begging for an azalea, camellia, or whatever bloom she saw in the family yard. She would convince the stunned homeowner that Bellingrath Gardens had been unable to locate one and then offer hundreds of dollars in an era when the U.S. Government declared that $25 per week was a comfortable income. She told a flower shop owner that her crocheted afghans were the most handsome she had seen and offered her $100 each for a dozen, knowing the money would put the woman’s niece in college, which it did.

Mrs. Bellingrath had a keen interest in antiques and collected from New Orleans to New York. Just as with azaleas, she always was ready to purchase an item brought to her porch in a car laden with children, paying top dollar for the family’s “treasure.” Antique dealers along famed Royal Street in New Orleans had few customers during the Depression and they saved their best for the lady from Mobile who never quibbled over a price. One dealer once admitted that when Mrs. Bellingrath arrived, prices doubled, but she never complained. She knew that her purchase might be their only sale of the week.

She had a great interest in her nieces and nephews, taking delight in her grandnieces and grandnephews as they visited. When one nephew admonished his young son for picking up one of this aunt’s breakables she overruled him. “Let him enjoy it,” she said. “If he breaks it, he breaks it. Don’t worry about it.”

Her household staff recalled her as always asking about their families and quietly handing out $20 bills for small tasks completed. She offered to help one young butler buy a car so he would not have to share a ride to work and he was astounded when she paid for the car in full. When he asked how much should be taken from his weekly paycheck her response was swift: “That was a gift, not a loan.” And as an afterthought, “Now, not a word!”

After her sudden death in 1943 at the age of 64, the Catholic Bishop called to console Mr. Bellingrath and to ask permission for a group of nuns to say a prayer as a way of thanks for all that she had done for them. As the couple had been Presbyterians, this surprised Bellingrath who asked, “How?” Without his knowledge, she had been sending flowers to the Catholic Providence Infirmary every week. The staff had been instructed to place fresh flowers in anyone’s room who did not have flowers sent by family or friends.

The Bellingrath Museum Home

Until 1934, Walter and Bessie Bellingrath had been residents of Mobile, where they maintained a beautiful home and garden at 60 South Ann Street. When they decided to have their weekend property open year-round to guests, the Bellingraths realized that it would require a great deal of supervision. The couple decided to establish residency at their now-famous Gardens, which were beginning to receive national recognition

The 15-room, 10,500-square-foot Home was built in 1935 and was designed by the prominent Mobile architect George B. Rogers.

The exterior features handmade brick salvaged in Mobile from the 1852 birthplace of Alva Smith Vanderbilt Belmont, who was a notable American socialite and a major figure in the women’s suffrage movement. Ironwork was obtained from the recently demolished Southern Hotel, also in Mobile. The result was dubbed “English Renaissance” by Rogers.

Flagstone terraces, a slate roof, and figural copper downspouts join with a central courtyard, balconies, and covered galleries to give the Home a Gulf Coast flair. The architect wanted the visitor to think of the house as a home, not a mansion, and it is situated to give the impression of a much more modest residence. He also wanted the Home to reflect the architectural heritage of the region.

The Home was the most modern of its kind in 1935, but Alabama Power had not brought electricity to this remote area of Mobile County. The Bellingraths therefore depended on a large Delco generator for electricity until 1940.

Continue Learning

Find out more about the history and construction of the Bellingrath Home with our narrated video below.

The Bellingrath Home appears as it did in the Bellingraths’ era and is open for tours. All of the Bellingraths’ original furnishings are on display to guests. Guests can enjoy seeing the “ultra modern” bathrooms of 1935, and the kitchen with its original appliances — German silver countertops and sinks — as well as the Butler’s Pantry overflowing with Mrs. Bellingrath’s collection of silver, crystal and china.

The Delchamps Gallery of Boehm Porcelain

The Bellingrath Home was adjoined by a guest house with a six-car garage beneath. Completed in 1939, it was built to accommodate the growing number of house guests invited to the Gardens by Walter and Bessie Bellingrath. A small chapel was included in its design, as well.

In 1967, the open garages were enclosed to become the Delchamps Gallery of Boehm Porcelain and a visitor’s lounge. This fine American porcelain collection was a gift to the Bellingrath-Morse Foundation by Oliver and Alfred Delchamps and their sister, Annie Delchamps Moore, who were long associated with the Bellingrath family. Their donation of rare and early porcelain sculptures by Edward Marshall Boehm has become the largest display of its kind in the United States.

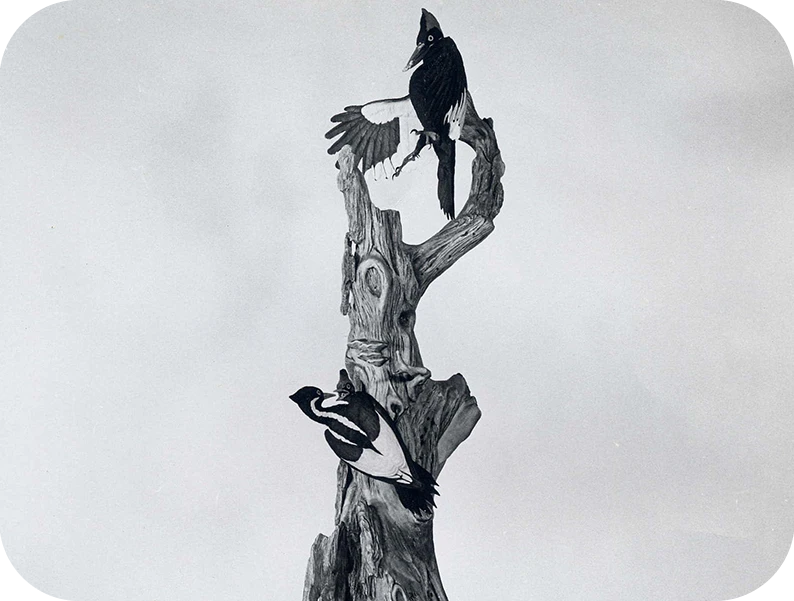

Edward Boehm started his porcelain artistry in 1949 after a career as a farm manager and veterinarian’s assistant. His deep love and understanding of animals of all kinds were translated into priceless porcelain sculptures featuring incredible detail and color.

In less than a decade, the Eisenhower administration had taken note of his unique American artwork and began a longstanding tradition of sending pieces of Boehm porcelain as official gifts to overseas dignitaries. Within a short time, his work was being admired from Peking to Buckingham Palace.

During his lifetime, Boehm was honored by commissions from five American Presidents, and his works were given to Pope John XXIII and Pope Paul VI. A duplicate of the crucifix given to the Vatican in 1959 is on display within the Delchamps collection.

Bellingrath is fortunate to house a collection that covers such a broad range of natural and beautiful subjects. Boehm’s birds amidst the branches of realistic flowers are a fitting compliment to the Gardens that surround them. As an art form, this collection represents the first successful American hard-paste porcelain.